Before we go any further, there’s something essential we need to make explicit – something my students taught me that changed everything.

Jake was brilliant at persisting. Give him any maths problem, and he’d grind through it with remarkable determination. But last Tuesday, I watched him spend forty minutes trying to force his way through a creative writing task.

“I just need to try harder,” he muttered, attempting his fifth revision of the same opening sentence.

His partner Emma leaned over. “Mate, this isn’t a keep-going problem. It’s a see-it-differently problem. Stop pushing and try a completely different angle.”

That’s when it hit me.

We’d spent so much time developing the Habits of Mind, but we’d missed something fundamental: students need to recognise which problems demand which Habits.

Emma didn’t just understand the Habits of Mind. She understood them as problem-solving superpowers – and more importantly, she knew which problems called for which powers.

The Superpowers Hidden in Plain Sight

For years, I’d been teaching the Habits of Mind as… well, habits. Important dispositions. Academic skills. But here’s the reality: students don’t care about “academic skills.” They care about solving problems. They care about getting unstuck. They care about moving forward when they’re frustrated, confused, or overwhelmed.

The Habits of Mind are what they are – but problem solving is what they do. That’s why we get so much more engagement, so much more buy-in, when we call them problem-solving superpowers. Students aren’t collecting skills for their CV. They’re building tools to handle whatever life throws at them.

Think about it from their perspective:

- Persisting isn’t just “not giving up” – it’s the Keep-Going Superpower that conquers problems requiring sustained effort

- Thinking Flexibly isn’t an abstract skill – it’s the See-It-Differently Superpower that unlocks problems with no obvious solution

- Managing Impulsivity isn’t about behaviour – it’s the Pause-Point Superpower that prevents costly mistakes

But here’s what we need to understand:

Students don’t wake up looking for opportunities to use their Habits of Mind. That’s not how life works. They wake up facing problems – a confusing maths question, a friendship conflict, a creative project that won’t come together. The problem comes first. Always.

So the real skill isn’t just having these superpowers. It’s recognizing which problem you’re facing, then activating the right superpower to solve it.

Problem recognition drives superpower selection. That’s the operating system we need to teach.

The shift seems semantic, but it’s seismic. When students see Habits as superpowers, they start asking the right question: not “Am I using the Habits?” but “Which superpower does this problem need?”

The Problems That Demand Powers

Here’s what Emma understood that Jake didn’t: every problem has a signature. A pattern that signals which superpower it demands.

Keep-Going Problems look like this:

- You know the general direction, but obstacles keep appearing

- Progress is slow but measurable

- The path may not be clear, but the goal is

- Success requires sustained effort through setbacks

- Each obstacle needs working through, not around

See-It-Differently Problems feel like this:

- Your usual approach isn’t working

- You’re stuck in a mental loop

- The answer might be hiding in plain sight

- Success requires fresh perspective, not more effort

Pause-Point Problems present like this:

- First instincts might be wrong

- Speed could cause mistakes

- Multiple options need consideration

- Success requires thoughtful choice, not quick action

Emma had developed what researchers call “problem recognition” – the ability to read a situation and activate the right cognitive response. It’s the difference between having tools and knowing when to use them.

At first, I wasn’t sure what I was seeing. But the more I listened to how students described their struggles, the clearer the pattern became. It wasn’t about trying harder. It was about trying differently.

The Alertness We Haven’t Been Teaching

Remember the Five Dimensions of Habit Development fromPart2? We explored Meaning, Capacity, Value, and Commitment. But it’s the fifth dimension – Alertness – that makes everything click.

Alertness isn’t just noticing when you need a Habit. It’s recognising which Habit matches which problem type. It’s the metacognitive skill that transforms reactive students into strategic problem-solvers. Alertness isn’t just about choosing the right Habit – it completes the five-dimension model of Habit development by making that choice deliberate, not default.

Once students recognise the problem type, they can step intentionally into the Learning Zone with the right superpower at the ready. They’re not just facing challenge – they’re facing it strategically.

Watch what happened when I made this explicit:

“Class, before you start today’s challenge, take thirty seconds. What type of problem is this? Which superpower will it demand?”

The shift was immediate. Students weren’t just diving in – they were diagnosing first. They’d moved from “What do I do?” to “What kind of problem is this, and therefore, what do I do?”

Marcus looked at his engineering challenge: “This needs precision, but also persistence when things don’t work the first time. It’s a Just-Right problem AND a Keep-Going problem. I need my accuracy superpower and my persistence superpower working together.”

Sophie examined her literature task: “There’s no single answer here. This is definitely a See-It-Differently problem. Time to generate multiple interpretations.”

They weren’t just using their superpowers – they were choosing them strategically.

The Complete Problem-Power Framework

Over years of classroom observation, these patterns became unmistakable. We’ve identified sixteen core problem types that consistently demand a specific Habit of Mind. Together, they form a teachable, transferable framework.

Here are just some of the problem-superpower matches:

Keep-Going Problems → Persisting

When the path is clear but challenging

See-It-Differently Problems → Thinking Flexibly

When the usual way isn’t working

Pause-Point Problems → Managing Impulsivity

When rushing risks mistakes

Just-Right Problems → Striving for Accuracy

When precision matters more than speed

Use-What-You-Know Problems → Applying Past Knowledge

When old learning unlocks new challenges

Ask-and-Wonder Problems → Questioning and Problem Posing

When you need better questions, not quick answers

But here’s the crucial insight: students don’t automatically make these connections. They need explicit practice in problem recognition, not just Habit application.

And there’s another layer: Real problems rarely demand just one superpower. Most require what I call a ‘critical cluster’ – two or three Habits working in concert. That engineering project? It needs persistence to push through setbacks AND flexible thinking to find new approaches AND striving for accuracy to ensure it actually works. The problem has multiple signatures, and students need to recognize and activate the full cluster.

From Recognition to Readiness

This brings us to an uncomfortable question: How do we know if students are actually developing their superpowers, or just using what they already have?

Remember from our journey: using a Habit isn’t the same as growing it. Students grow when they’re in the Learning Zone – that sweet spot where they’re stretched just beyond their current capability but not overwhelmed. But how do we know which zone they’re operating in for each Habit?

That’s the missing measurement. And it’s exactly what we discovered Sophie needed.

The Zone Mapping That Changes Everything

This is where traditional Habit assessments fall short. They ask “How well do you persist?” but miss the crucial question: “Are the problems you normally face actually developing your persistence?”

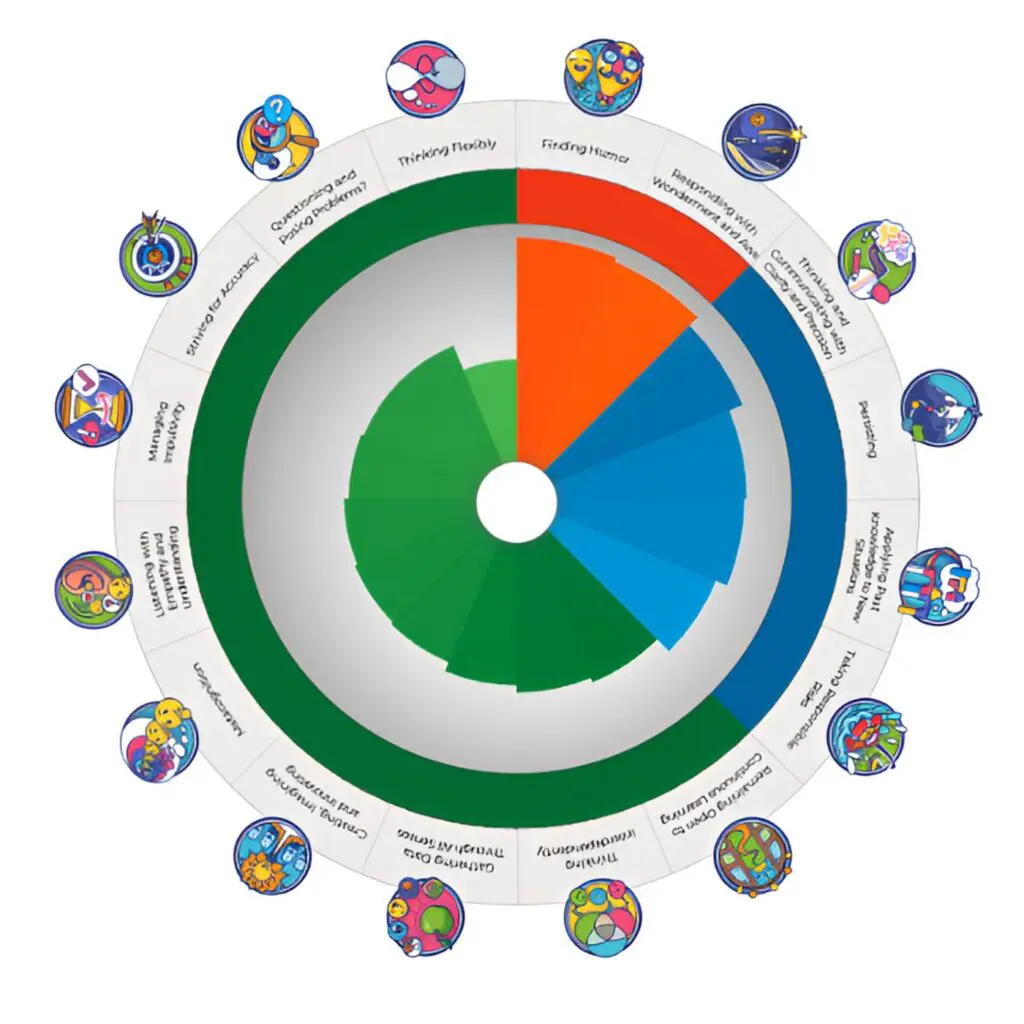

That’s why we developed the Habits of Mind Learner Profile – a revolutionary assessment tool that doesn’t just measure how well-developed your Habits are in isolation. Instead, it asks the question that actually matters: “Are your Habits well enough developed for the problems you regularly encounter?”

Think about it: A Year 3 student and a Year 12 student might both be “good at persisting” – but they face completely different problems. The Profile assesses your Habits relative to your actual challenges, revealing where you’re truly positioned for growth.

The Profile identifies which zone students typically work in for each Habit:

- Comfort Zone (Orange): Problems feel easy. Students cruise through using existing skills. Well within current abilities. No growth happening.

- Performance Zone (Blue): Problems are well matched to students current abilities. They’re demonstrating the Habit but not developing it.

- Learning Zone (Green): Problems stretch students just beyond current capability. They must develop new strategies. This is where growth lives.

- Aspirational Zone (Red): Problems are too far beyond current capability. Students feel overwhelmed and can’t engage productively.

Here’s what’s crucial to understand: Comfort Zone performance often looks successful – but success without stretch is comfort without growth. A student breezing through tasks isn’t lazy; they’re undernourished by challenge.

The Profile presents students with scenarios that demand each Habit, then maps their responses to reveal their operating zone. It’s not about how good they are – it’s about whether they’re positioned for growth.

Making Vulnerabilities Visible, Making Growth Strategic

When Sophie took the Learner Profile, the results perfectly explained her struggles. This isn’t just for students – it gives teachers a clearer picture of where to target challenge, design feedback, and support growth. Together, Sophie and I reviewed her zone map:

The Profile’s color-coded visual made everything clear at a glance. Orange zones showed where she was coasting, blue zones revealed where she was working hard without growing, green zones highlighted where real development was happening, and any red zones would indicate areas currently beyond her reach.

Operating in Learning Zone:

- Striving for Accuracy (actively developing new precision strategies)

- Managing Impulsivity (learning new ways to pause and think)

Cruising in Comfort Zone:

- Finding Humour (avoiding situations that require it)

- Responding with Wonderment (not encountering awe-inspiring challenges)

Aspirational Zone

- Thinking Flexibly (rarely facing problems that demand it)